I am a citizen of the world, known to all and to all a stranger – Desiderius Erasmus

For many today the name Erasmus conjures up images of students basking in foreign cultures while they further their education abroad. Unknown too many these globetrotting scholars are following in the tradition set down by one of Europe’s most important and influential thinkers. Born in Rotterdam toward the end of the 1460s Desiderius Erasmus came to embody the perpetual student and academic as he travelled throughout Europe championing humanism and humanist education.

Today his name is attached to a series of programmes and organisations that promote international learning and education. Yet Erasmus’ legacy and impact reaches far beyond the walls of educational institutions. His pioneering of the printing press and prolific writings and translations made him one of the most important figures in the Northern Renaissance and European Reformation. Simply put, the world we live in today would be wholly different were it not for Desiderius Erasmus.

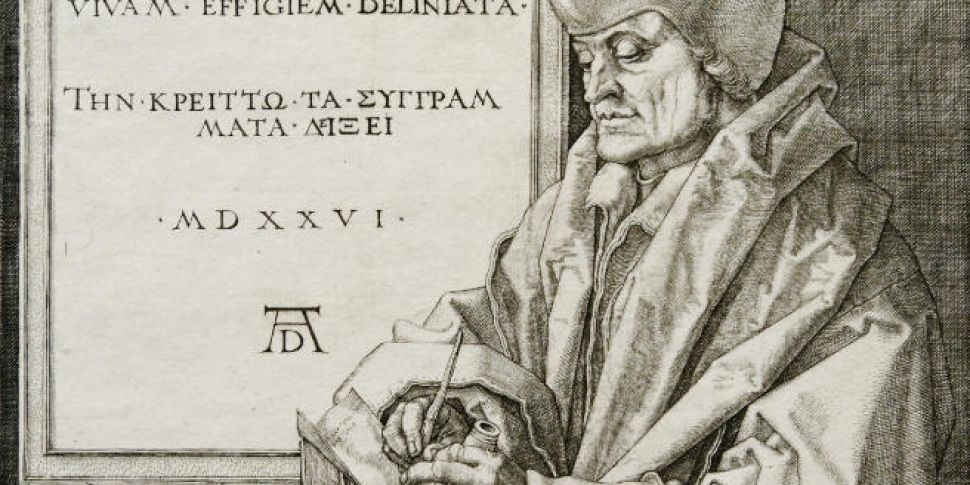

Studies of the Hands of Erasmus by Hans Holbein the Younger, circa 1523

Studies of the Hands of Erasmus by Hans Holbein the Younger, circa 1523

While much of Erasmus’ youth is unclear, including the exact year of his birth, we do know that he was the illegitimate child of Margaret, a physician’s daughter, and Roger or Gerard, a priest in Gouda. At an early age Erasmus was sent with his older brother Peter to a grammar school in Deventer. His mother moved nearby to tend the children as they learned at this institution run by St. Lebwin’s church. Here Erasmus received a good education in Latin which would go on to form the foundation of his later life.

More important than the school’s sound education in Latin, however, was its progressive streak. Toward the end of Erasmus’ time there a new headmaster, Alexander Hegius, arrived. His interest in the humanistic thought flourishing in Italy at this time saw Hegius bring these pioneering theories and ideas, which prioritised man's individuality and the study of original sources, to his new posting. This proved to be the beginning of Erasmus’ humanist education which would ripple through the rest of his life and education.

This life of learning wasn’t destined to continue in Deventer, however, as the city fell victim to the plague in 1483. The two brothers went to live with their father in Gouda after their mother fell victim to the disease. This brutal blight followed the boys and they soon found themselves orphans as their father succumbed to the same fate as their mother. Left in the care of three guardians Erasmus found himself in a period of limbo as he repeated the education he had already received.

Marginal drawing in the first edition of Erasmus 'Praise of Folly' by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1515

Marginal drawing in the first edition of Erasmus 'Praise of Folly' by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1515

Unwilling to invest too much in the brothers, Erasmus’ guardians shipped the boys off to another grammar school. Illegitimate and without a university education the career paths open to Erasmus and Peter were limited and their guardians pushed the boys into taking monastic vows. Though they initially resisted both soon relented and Erasmus became an Augustine novitiate around 1487. The monastic life would prove complicated for Erasmus.

He thrived on the intellectualism in the close community yet was stifled by the order’s strict regimentation of his life. This dichotomy is fairly evident in his earliest works penned during this time. The result of communications with his fellow monks these works paint a nice picture of monastic life yet rile against its constrictive nature and discourage boys from joining at a young age. In 1492 this complicated relationship reached its zenith when Erasmus became an ordained priest.

Though it tied him inextricably to his vows ordainment allowed Erasmus to pursue the freedom he craved. An accomplished man of letters with a strong grasp of Latin Erasmus came to the attention of the bishop of Cambrai, Henry of Bergen. His standing as an ordained priest allowed him to serve as Henry’s secretary and in 1493 he left the monastery; he would never return, even when officially recalled later in his life.

Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523

Portrait of Erasmus of Rotterdam by Hans Holbein the Younger, 1523

An ambitious political animal Henry had hoped his family ties would see him elevated to the College of Cardinals. As this dream faded away Henry lost interest in his accomplished secretary. While Erasmus had been attracted to the freedom this new posting offered the politicking left little time for academic study. As a result he found himself despondent of his posting and petitioned Henry to send him to Paris to study.

While Paris afforded him strong learning opportunities Erasmus was unimpressed with the harsh conditions and embedded theological traditions. During his time there Erasmus drifted further and further away from the established doctrines and embraced the humanism he found flourishing around France and Italy. This predilection for the unconventional would become a vital part of Erasmus’ character and legacy.

Paris had increasingly become a trail for Erasmus. Poverty had forced him to endure harsh conditions while studying while Henry’s neglect of his charge saw Erasmus take up tutoring to pay his way. While he never seems to have planned on becoming a teacher Erasmus proved an able one. In 1499 one of his most important students and friends William Blount, Lord Mountjoy, returned home to England and welcomed Erasmus to join him there. Here Erasmus enjoyed a life free from poverty and, more importantly, encountered an academic world obsessed with the learning of Greek and the challenging of prescribed dogmas through informed study.

Map of Thomas More's Utopia by Abraham Ortelius, circa 1595

Map of Thomas More's Utopia by Abraham Ortelius, circa 1595

In the first of his many important works, Handbook of the Christian Soldier, Erasmus sketched the foundations for his philosophia Christi. This theory argued that Christianity must be a way of life and that Christ’s spirit must permeate every action and facet of a Christian’s life. This idea remains a strong school of thought in Christianity to this day. At the time it saw Erasmus’ star rise as it fed into his growing reputation around Europe as one of the world’s leading humanist thinkers and writers. Upon his return to the European mainland Erasmus began to the poor student life afresh as he eagerly sought to master the Greek language. Despite a poor teacher and the handicap of poverty by late 1502 Erasmus boasted a fluency in Ancient Greek. This allowed him to read and compare religious and biblical works and, most importantly, comment authoritively on them. This increased interest and ability in theological studies would see Erasmus catapulted into the centre of European and ecclesiastical affairs as the Reformation took root and began to tear Christendom apart.

This argument for Christianity as a way of life saw Erasmus openly criticise the Catholic Church and its aloofness. He had unknowingly become one of the chief architects of the Reformation as his writings and thought paved Luther’s path to the door of the Castle Church of Wittenberg. In contrast with Luther, however, Erasmus refused to break with Rome. Instead he stood with his close friend Sir Thomas More as an advocate for peaceful change from within.

Sir Thomas More bidding farewell to his daughter Margaret Roper

Sir Thomas More bidding farewell to his daughter Margaret Roper

Unlike More, however, Erasmus’ convictions would not cost him his life. Whether this was a blessing or curse could be argued. While More’s martyrdom saw him immortalised in Sainthood Erasmus was forced to continue his life as a progressive humanist in an increasingly inhuman world. His early progressivism and defence of Luther stood as a mark against Erasmus in Catholic eyes. His public break with Luther and open criticism of emerging protestant churches, however, put him at odds with many Protestants.

Though condemned by many on both sides for walking the middle path, Erasmus also enjoyed bilateral support from the more moderate camps also. While this support allowed Erasmus to enjoy his twilight years the passage of time brought more extreme and conservative elements to prominence across Europe. In 1559 Pope Paul IV placed all of his works on the papal index of forbidden books. Similarly many Protestants maintained Luther’s assertion that Erasmus was an atheist, a hypocrite, a snake, and lacked any true religious faith.

Erasmus’ legacy would survive in large part thanks to the more moderate elements of European Protestantism and the Church of England. Today he is regarded as one of the most important thinkers of the Northern Renaissance, a revolutionary theologian, and one of the defining forces of the Reformation.

Print showing Luther burning the papal bull of excommunication, with vignettes from Luther's life and portraits of other Reformers

Print showing Luther burning the papal bull of excommunication, with vignettes from Luther's life and portraits of other Reformers

Join ‘Talking History’ as we delve into the life, writing, and legacy of Desiderius Erasmus. Why is he regarded as the crowning glory of the Christian humanists? Was he truly a protestant at heart or merely a Catholic intent on reform? What has his ultimate contribution to the world been?