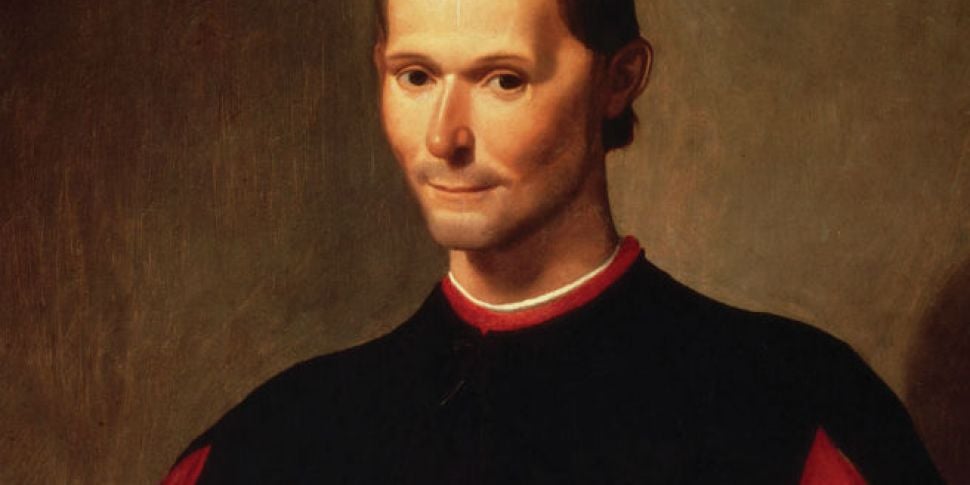

...in the actions of all men, and especially of princes...one judges by the result - Niccolo Machiavelli The Prince 'Chapter XVIII'

In 1532 Niccolò Machiavelli's The Prince was published. Though the author had been dead for five years at the time of first publication, this work would see to it that he wouldn't be forgotten. Today Machiavelli is, arguably, one of the most important and influential thinkers of all time; all thanks to this manual on how a prince should properly rule and act. Yet this political handbook, lauded and studied by so many, might be little more than political satire. So what is The Prince? What does it say? And what has its legacy been? -Padrão dos Descobrimentos

-Padrão dos Descobrimentos

The 15th and 16th centuries were one of the most important times in European and world history. The discoveries and improvements to culture and technology during this time would change the world forever as European powers rose to the fore and began their conquering of foreign lands. As prosperous as these centuries were, however, they were far from peaceful. Politics were in constant flux and, with power vested in those who could hold it by force, might generally proved to be right.

This was most evident in Italy as popes, kings, emperors, and all other variety of political power vied for control over the hodgepodge of Duchies, Kingdoms, Republics, and various other states that made up the Italian Peninsula. Mercenary armies marched under ever-changing banners while at home politics was negotiated under the bed sheets and by assassin's blades. It is not surprising then that it would be from the Italian states that the magnum opus of pragmatic politics would emerge. -Charleville-Mezieres Siege de 1521, Gustave Toudouz

-Charleville-Mezieres Siege de 1521, Gustave Toudouz

Born in 1469 Machiavelli grew up in a Florence dominated by the Medici family, with the immense figure of Lorenzo 'the Magnificent' at their head. The Medici were symptomatic of Italy at large during this time as individuals and families battled for prominence and territory with their armies of mercenary soldiers. It is impossible that Machiavelli was unaffected by these conflicts and prominent figures like those who lead the houses of Borgia, de Medici, and Sforza were surely the inspiration and target audience for The Prince.

Without the events of the 1490s, however, Machiavelli would be unremembered today. After the death of Lorenzo in 1492 the Medici family was lead by Piero 'the Unfortunate'. Two years after inheriting his father's legacy Piero and the Medici were expelled from Florence and the state's old status of Republic was reinstated. The same year as the Medici expulsion another death, this time Ferdinand I of Naples, heralded decades of war in Italy as Charles VIII of France laid claim to the Kingdom of Naples with an invasion force of 25,000 men. -French troops under Charles VIII entering Florence, Francesco Granacci

-French troops under Charles VIII entering Florence, Francesco Granacci

Thus the 15th century ended with the Italian Wars in full swing and Machiavelli in the post of Chancellor and Secretary to the Second Chancery, the Ten of Liberty and Peace. This body was charged with overseeing the military matters and foreign affairs of the Republic of Florence. As such Machiavelli was at the centre of Florentine politics and found himself dispatched on numerous diplomatic missions. It was his interactions with political figures of Europe during these missions which helped form Machiavelli’s key theories on princely behaviour.

Pope Alexander VI and his son Cesare were, however, Machiavelli’s greatest muses. These men gained infamy for their unhesitating use of all means available to expand and consolidate the power of the Borgia during the 15th and early 16th centuries. This pragmatic separation of politics and ethics reflects key characteristics of Machiavelli’s ideal prince. Papal support, however, proved integral to Cesare's career and he fell from grace only a few years after the death of his father, Alexander VI. This would also, indirectly, end Machiavelli’s political career. -Cesare Borgia leaving the Vatican, Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri

-Cesare Borgia leaving the Vatican, Giuseppe Lorenzo Gatteri

In an attempt to reconcile with an old enemy Cesare used his influence to have Giuliano della Rovere made pope in 1503. This was a cardinal mistake for a Machiavellian prince and della Rovere’s enmity toward the Borgia didn’t slacken after he took the name Julius II. By 1507 Julius had stripped Cesare of most of his territory and this once great prince died on the battlefield a simple mercenary captain.

A behemoth of the international stage Julius was central to both the League of Cambrai and the Holy League. The victory of the Holy League in 1512 ended the Florentine Republic as Julius II insisted the Medici be reinstated as princes of this city state. Machiavelli fell with the republic. In the years after his fall Machiavelli began to publish writings on politics and political theory. In 1513 Machiavelli published an early version of The Prince dedicated to Lorenzo de Medici, the new prince of Florence. This work, De Principatibus, extolled the virtues of pragmatism in politics and made a clear argument that ethics had no place in palaces or parliaments.

These attempts to rebuild his political career were, however, fruitless and Machiavelli never again regained a strong political position; though he did receive some work from later Medici. What this campaigning did achieve, however, was the establishment of Machiavelli as an intellectual force of the time and one of history’s most important political philosophers. Today The Prince is seen as the dictator’s guidebook and a blueprint on how to achieve success and power in the world.

Figures from Thomas Jefferson, to Napoleon, to Mussolini and many diverse others have lauded this political work. For many, however, Machiavelli’s divorcing of ethics from power in The Prince has left a terrible legacy that can still be felt in self-serving politics today. What is often overlooked, however, is the design behind Machiavelli’s magnum opus and what this Italian intellectual thought to achieve in its publication.

The Prince is at odds with a modern democracy and naturally jars with people today. In its pages Machiavelli clearly states that it is better to be feared than to be loved and that the ends justify the means. This is anathema to a peaceful democracy with strong social institutions. Today we expect our leaders and representatives to act morally with the explicit aim of furthering the needs of their people.

As its title indicates, however, The Prince is a book on how a prince should properly comport themselves and their affairs. This is not a book about democracies and explicitly sets out from the start to demonstrate the best ways one can take and hold new territory. Considering the political climate Machiavelli was writing in this attitude is quite understandable. Surrounded by a state of almost constant war and intrigue Machiavelli had personally witnessed how easily any state could fall to internal-sedition or armies of mercenary soldiers. -After the Battle of Marignano, Urs Graf

-After the Battle of Marignano, Urs Graf

In The Prince Machiavelli turned to contemporary examples to demonstrate ways in which politicians can succeed or fail. Catherina Sforza is held up as an example of how the goodwill of the people can be as strong as or stronger than any martial force in holding territory. Louis XII is used as an example of how a successful conqueror can fail at holding and securing their prizes. Machiavelli even uses Ferdinand II of Aragon to demonstrate how religion and faith can be used as a tool in the pacification of conquered territories.

Considering the land Machiavelli lived in was so bathed in violence it is easy to forgive him his pragmatic political philosophy; especially as he was seeking employment with the reinstated Medici at this time. Yet in Discourses on Livy Machiavelli speaks highly about republican ideals and the running of a republican state. He also emphasised the importance of civic duty and campaigned for the raising of militias who would be loyal to the state as opposed to some independent paymaster. This republicanism flies in the face of the popular image of Machiavelli as a proponent of totalitarianism.

Listen back as Patrick and a panel of expert unwrap the story of The Prince. What was Machiavelli's aim in writing this book? Can we defend the totalitarian philosophies expressed in The Prince? Or should they be relegated to a bloodier time in history? Was The Prince even meant to be taken as a serious work or is it a satirical joke that has gotten out of hand?